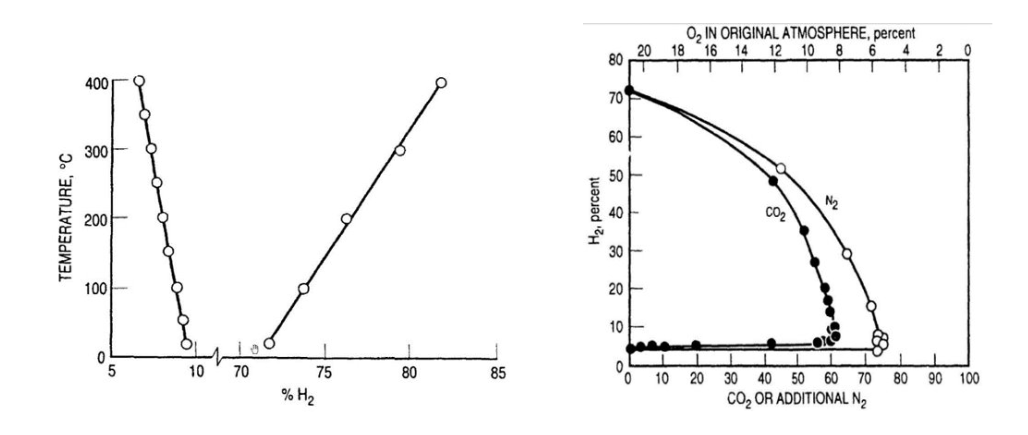

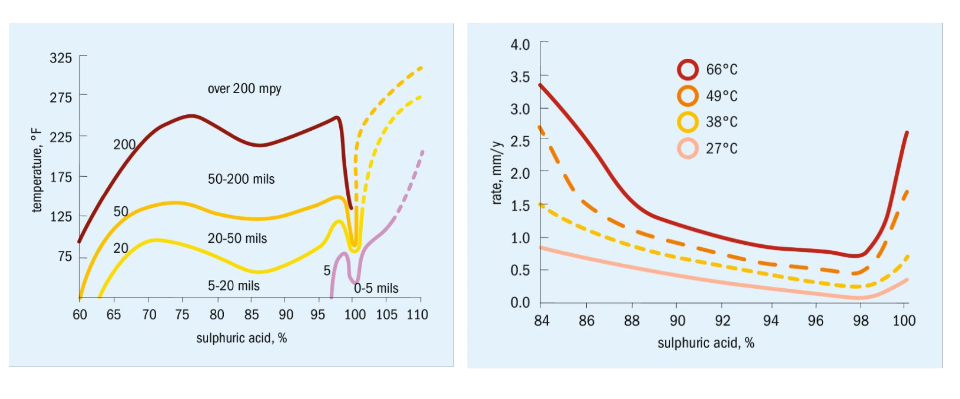

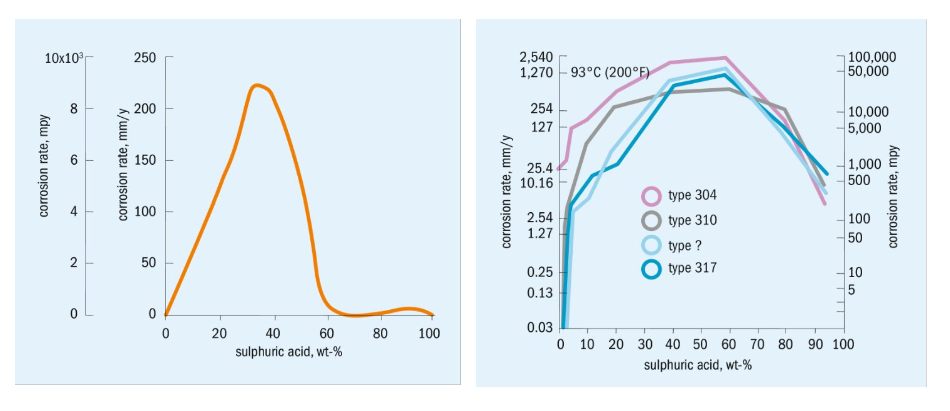

Based on those data, the amount of hydrogen generated can basically be determined, at least as an order of magnitude. For example, the corrosion rate of a 1000 m² heat exchanger when exposed to 100 degrees C acid at 80 percent H2SO4 is in the range of 10 mm/year. Low alloy stainless steel, e.g. 304 or 316 type, offers slightly less corrosion, but still in the range of 6 mm/year.

If such a heat exchanger is exposed to 80 percent acid at 100 degrees C for about 4 hours, then the amount of hydrogen produced would amount to 37 kg or 406 Nm³.

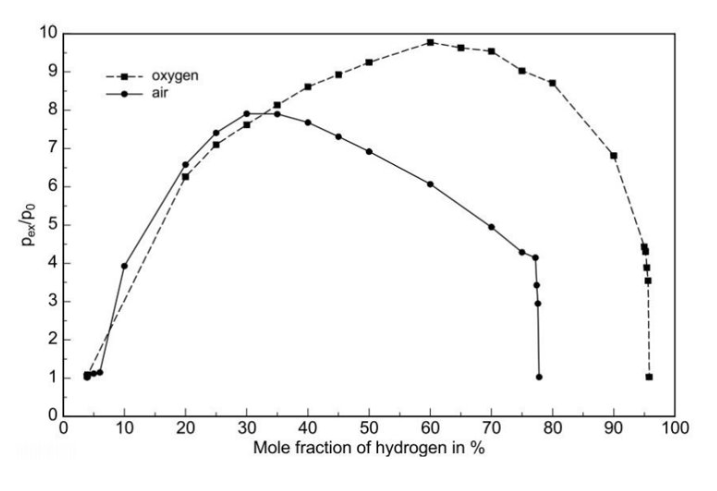

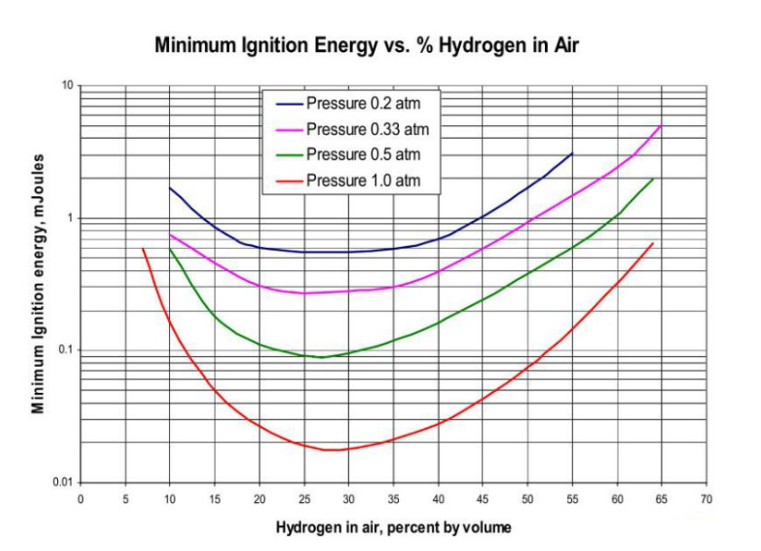

When a plant is idle for such time and the hydrogen accumulates at the top of the intermediate absorption tower, which may have a volume of 700 m³ (or even less when considering only the “dead” volume on top of the gas exit duct, say 150 m³), then the H2-concentration can be anywhere from 50-100 percent. The rest of the gas obviously must contain some oxygen, which is the case when <100 percent H2 is present. These figures are well within the range to generate an explosion, provided that sufficient oxygen is present.

Obviously it has to be considered that such an explosive mixture could accumulate—depending on the plant configuration—in other areas. For example, in one reported case the explosion occurred not in the top of the tower, but below the candle filter tube sheet.

Normal variation or excursion of acid concentration during operation

The earlier example and case studies clearly show that such events occur only under atypical conditions. It has to be understood that variations of acid concentration at normal operation, e.g. failure to control process water addition, can be regarded as non-critical with regard to the potential formation of hydrogen as a result of corrosion. Despite the higher corrosion rate as a function of operating outside the pre-determined design figures/operating windows, and as long as the possible material window of concentration and temperature are adhered to, the potential amount of hydrogen formed is negligible.

It can be concluded that:

- The small amount of H2 will not reach the explosion range during operation.

- Normal operation offers a gas composition where the O2 content is very low.

- By having a continuous gas flow through the plant, the hydrogen concentration will be negligible and well below the lower explosive limit.

Operating windows are to be determined in accordance with process boundaries, e.g. an absorber cannot be operated outside of 98.0-99.0 percent H2SO4 and a drying tower not outside of 92-98.5 percent H2SO4, without generating other detrimental effects, such as extreme SO3 plume or heavy condensate formation. Obviously such circumstances would force a plant shutdown prior to entering into the tolerable material window.

The material window is defined to be the range where the corrosion rate is still tolerable for a short period of time (up to, say, 1 mm/year), despite being the typically acceptable range of 0.1 mm/year.

As long as operation parameters are contained within said limits, one must not expect an exceeding formation of hydrogen during operation. Shut down conditions are very different, however, as the hydrogen may accumulate and thus form an explosive composition.

Plant and equipment design considerations

It is a given that, in every plant, equipment can fail due to nearing the end of operational life, malfunction or defect. For the formation of hydrogen, the equipment that causes excessive water ingress is most relevant. That equipment is mainly steam related (waste heat boilers, economizers or superheaters) or water related (acid coolers or water dilution control valves).

As explained earlier, hydrogen is formed by the reaction of weak and/or hot acid with stainless steel, e.g. acid coolers, economizers, stainless steel towers, piping and other metallic components. The formed hydrogen will find, in every plant, stagnant areas where gas can accumulate and form an explosive hydrogen/oxygen/process gas mixture.

As all of that equipment is required and the plant layout will not allow an elimination of those stagnant areas (e.g. in one reported incident, the hydrogen reacted below the tube sheet), different measures that can be taken during design or operation to minimize risk need to be discussed. Of course, based on the studied cases, there are contributing factors to consider. For example:

- Delayed leak detection, e.g. due to leak size or not maintaining/installing instruments.

- Inability to isolate/separate the water from the acid system.

- Inability to remove weak acid from the system, which causes further corrosion.

- Insufficient operation manuals addressing such events.

Keeping those generic aspects in mind will certainly help to increase the awareness of the issue of hydrogen incidents. The expert committee elaborated on more specific high level considerations. Those considerations should serve as a help for designers, operators and consultants in the sense of …am I aware of the potential consequences… or …have I considered that…..

Please note that obviously such a list cannot cover all the specific elements of a plant, equipment, etc., and is meant as a list of typical considerations that complement rather than replace design guidelines, operation manuals or procedures. Such plant-specific documents can and should be expanded with regard to the hydrogen issue during the respective project-specific discussions.

High level considerations

Avoiding hydrogen formation

The mechanism of hydrogen formation is well understood, as described earlier. It is crucial to transfer this knowledge into the design and operation in order to minimize the risk of hydrogen formation, which actually means avoiding rapid corrosion. It is of utmost importance to consider the entire plant/operation and understand potential effects of local modifications to other plant areas.

- Consider the characteristics of construction materials:

- Bricklined vs. stainless steel towers/vessels (material resistance, drain concept, etc.).

- Cast iron vs. stainless steel equipment (irrigation system, piping, etc.).

- Ensure separation of weak acid from metallurgical surfaces, for example:

- Drain acid from acid coolers; consider drain valve location and size of valve and ensure drain piping is sufficiently dimensioned.

- Acid can be drained from other stainless steel equipment, e.g., towers, pump tank, piping, etc.

- Acid distributors, tube sheet can be drained to avoid risk of local hydrogen formation.

- Minimizewateringressusingthese designconsiderations:

- Cooling water isolation.

- Boiler feed water bypasses around economizer.

- Consider measures to identify water ingress early on, for example:

- Additional instrumentation to measure, e.g., dew point and opacity.

- Intelligent data management system for analyzing flow rate, temperature, production deviation, etc.

- Consider related infrastructure in plant safety concept/HAZOP studies, especially the cooling water system:

- Ensure that water pressure is always lower than acid pressure.

- Ensure that acid contaminated cooling water can be drained.

- Ensure cooling water quality is monitored.

Avoid hydrogen accumulation

The key to safe operation is avoiding hydrogen formation. However, one has to consider that despite all efforts, the risk of hydrogen formation exists–even only nominally. Hence the design of plant/equipment as well as operational procedures must take this into consideration.

- Use these design considerations to minimize areas of potential hydrogen accumulation:

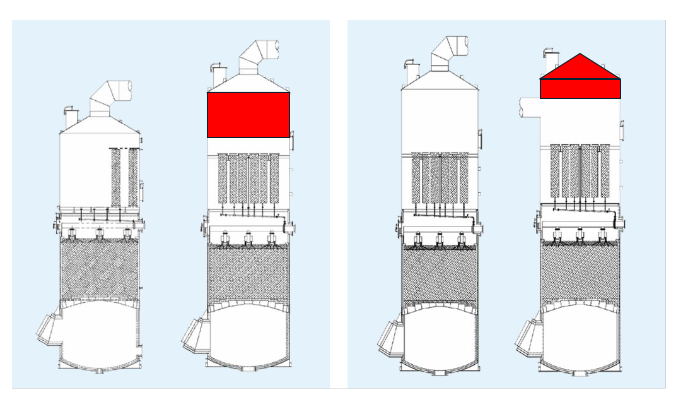

- Fit acid tower with top, not lateral, gas outlet.

- Minimize volumes of gas accumulation through the design of the equipment, see example later in this article.

- Ensure that proper shutdown and purge procedures are in place:

- Those procedures have to be established considering the individual plant characteristics and local standards.

- Potential procedure: ongoing purging of the plant by main blower following an event, until all weak acid is removed from system and equipment is isolated.

- Minimize potential H2 accumulation by, for example:

- Purging blower.

- Installing high point vents.

- Purging nitrogen (depending on local infrastructure).

Equipment specific aspects

Equipment design and operation should consider specific aspects for risk mitigation. Listed below are three examples of equipment that represent prominent sources of hydrogen formation, accumulation and ultimately explosion. Please note that equipment other than those listed could also be analyzed in a similar fashion.

Acid coolers

Acid coolers offer a huge surface area, and hence have the highest potential for hydrogen formation. However weak acid in cooling water circuits can also result in hydrogen formation in the respective equipment (e.g., air coolers with closed loops). Consider the following aspects of acid cooler operation:

- The main reason for an acid cooler leak is related to water quality.

- Is the cooler chosen for the cooling water quality?

- Does the actual and the specified quality of the cooling water match?

- Is the cooling water quality regularly monitored and are treatment procedures in place and maintained?

- The acid pressure should be higher than the water pressure.

- While this is correct at start-up, is this still valid after years of operation?

- How is this considered/mitigated at heat recovery coolers/evaporators, where this demand can generally not be adhered to?

- How is this ensured in abnormal situations, e.g., acid pump shutdown, filling of tanks etc?

- As plant capacities increase, acid coolers are getting larger.

- Is the increased capacity considered in the design?

- Is the drain number and size correctly dimensioned?

- Is a vent valve installed to support faster drainage?

- Where are water and acid drained to?

- Is the maintenance of acid coolers done in a proper way?

- Are there procedures available and are personnel aware of them?

- The washing of coolers can result in:

- Residual water in plugged tubes. Note: Tubes can be blocked by fouling on the water side, which creates a corrosive environment (hot spots).

- Residual water in the shell.

- Is an adequate leak response ensured?

- Can the water side of the cooler be isolated and drained?

- Are the drains/vents easily accessible even during upset conditions?

Economizer

In economizers the water pressure is always significantly higher than the gas pressure, so a leak will force water into the gas stream. Once water has entered the gas stream weak sulfuric acid will potentially be formed. The result can be rapid corrosion (hydrogen formation) of the finned tubes and other downstream equipment.

- Water entering the gas stream can end in acid towers and dilute the acid strength.

- Consider draining the economizer.

- Bottom drains can easily be blocked by small debris or sulfate.

- Is it part of maintenance practice to inspect such drains at every shut down?

- Is there a safe location to drain to?

- Are upset operations and cool down phases adequately considered?

- Can the water side be fully isolated?

- Is a gas or water bypass around the economizer needed for the cool down procedure?

Absorption towers

Irrespective of a leak occurring in an economizer, waste heat boiler or acid cooler, ultimately the water will enter the absorption tower, eventually resulting in circumstances where the acid strength can’t be controlled anymore, hence the sub-system of the intermediate absorption tower is the area of the highest potential for hydrogen formation.

- What are implications of construction materials?

- Stainless steel towers are easy to install, however they offer a reduced operation window. Can it be ensured that the towers can be drained in case of upset operation (weak acid)?

- Bricklined towers are significantly more robust and less exposed to corrosion and so weak acid could remain stored in the tower sump or pump tank for some time. Has the material decision been triggered by the draining concept?

- Consider a design to minimize vapor and stagnant gas spaces.

- Consider standing vs. hanging candle filters, as in Fig. 9.

- Consider top vs. lateral gas outlet, as in Fig. 10.

- Consider the maintenance concept: in-tower candle replacement vs. cutting of roof.

- Consider options to remove hydrogen from the potential areas in the tower:

- Purging using main blower after acid pumps are out of operation.

- Purging using nitrogen (if available).

- Purging using high point purging vents.